(This is the first in a series of posts on data strategy. Next post here.)

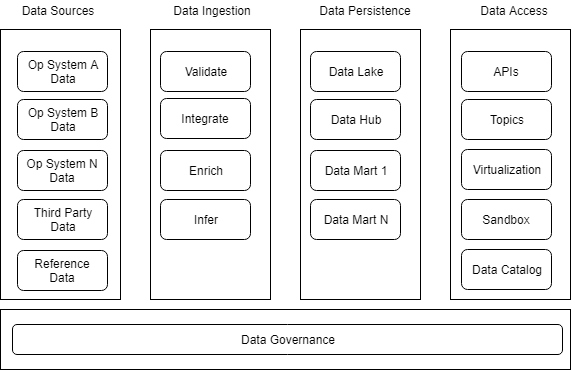

I’ve been reviewing and providing feedback on a number of data strategies lately, each presented as a future state ‘conceptual’ architecture which is mixed-level-of-abstraction Dagwood technology sandwich with an implied left-to-right flow. You know the kind of diagram I mean:

The diagrams have been nearly identical, as has my feedback. Seems like a common pattern, so I thought I would share it.

These future state conceptual data architectures are simply not aggressive enough – succeeding in our 24x7x365, near-real-time, Internet-of-Things fueled, consumer-driven future demands that we take advantage of the faster processing and higher network bandwidth available today – and more available tomorrow – to abandon the reactionary database-first data architecture approach we have been saddled with since IBM and the Seven Dwarfs ruled the roost and adopt instead an approach where events are fundamental.

The conceptual tidal wave of the need for huge volumes of aggregate data to support analytics that we have been inundated by, fertilizing Chief Data Officers to pop up across the landscape like so many mushrooms, is still washing over us, and driving our near-term data strategies.

A key question that reveals the shortcomings of the common current approach is, “how does the architecture handle operational data, not just analytical data?”. If the answer is not clear, the architecture is inadequate. And when the analytics data wave breaks, we – the health payers and providers we – are all going to be left with data solutions that won’t be competitive with the Havens now on our bumpers.

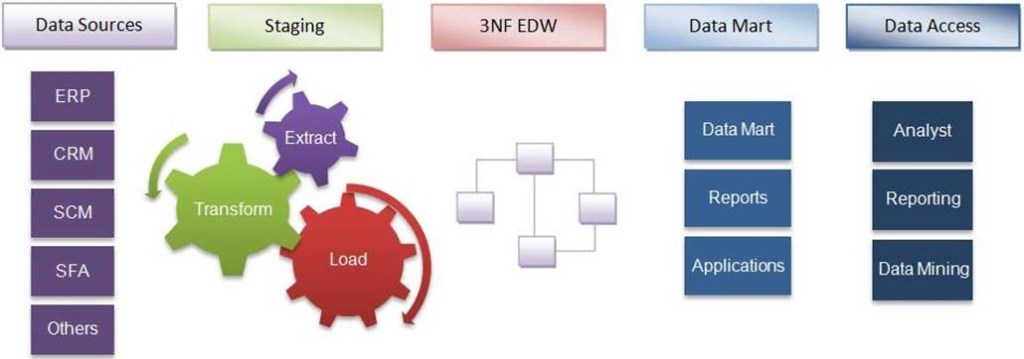

Historically operational data and analytic/reporting data were two separate things. Operational systems created operational data, which tended to be dirty and inconsistent. Reporting/analytics needs clean, consistent data. So we tossed the operational data over the silo wall in batch files, and ran it through our Kimball/Inmon warehousing processes, which scrubbed it, buffed it, tied it together, and stored it in a contrived format (‘denormalized’) to make analytics faster.

But compare the picture above to a classic Bill Inmon data warehouse architecture circa 1991:

There are no substantive differences – the models I have been reviewing have been classic Inmon models with coats of new-technology-buzzword paint.

What should the future state look like? That deserves a long answer, which I intend to deliver here soon, but a snapshot might go something like this:

A future state data architecture must be based on ‘event sourcing’. Streams of events – notable changes in state – to entities of interest, such as patients/members and claims, should be persisted in distributed, append-only logs. Those logs become the source of truth about the entities. Aggregate datamarts to support analytics may be created at will if needed by ‘replaying’ those logged events into databases. The integration of events across the logs is achieved by having the events all conform to an overarching national health care ontology – a consistent model of the concepts of health care, their relationships, and the invariant rules that govern their lifecycles.

Why are we still seeing database-based models? Historically we did not have the processing speed and network bandwidth to enable an event sourcing approach. The implementation concessions that were first made in the 1960s still make up the model we are familiar with today: events about an entity are stored up locally for a day or a week, then collected into a file (‘batch file’) and sent all at once to a discrete physical location, where they are applied to a persistent snapshot of the entity in a database to bring it current. That overall process is the familiar ‘ETL’, or Extract, Transform and Load.

Key problems with that approach? The snapshot is always out of date, it is just a question of how far. And, typically, the snapshot does not store the history of changes – only the most recent one. Neither one of those gets it done in our 24x7x365, near-real-time, Internet-of-Things fueled, consumer-driven future.

What is changing is that the cleaning and consistency part is being pushed forward into the operational systems and the events that stream from them, and, at the same time, the aggregation required for analytics is beginning to be done more and more on the fly, powered by distributed processing in the cloud.

The future state model we need must begin independently of those legacy physical concessions. What is the conceptual bedrock? The real world (people and things, biological relationships, etc.) and virtual world (orders, contracts, legal relationships, etc.) are instrumented so changes in them can be observed and reported. Those reports are validated, normalized, and recorded for posterity. That’s where data comes from and where a future state model needs to start.

It no longer makes sense to have discrete operational and analytics data strategies: there must be only one. And that one can’t start with databases. It has to be based on data at its most atomic level. And the atoms are events.

(I expand on these ideas in the next post in this series.)

Stay tuned.