This is the second part of a series describing the Command, Notify, Query (CONQUER) distributed systems architecture: distributed systems are information tools enabling volitional entities in relationships of permission and obligation to achieve their ends via purposeful dialogs, communicated among software components proxying their wills, consisting of imperative, declarative, and interrogative sentences: commands, notifications, and queries. First Part. Previous Part. Next Part.

To start our deep dive into the rationale for the CONQUER architecture let’s go back to the late 13th century…

…and St. Thomas Aquinas’s first mover argument for the existence of God:

- Nothing can move itself.

- If every object in motion had a mover, then the first object in motion needed a mover.

- This mover is the Unmoved Mover called God.

So who moves our great information technology systems, these epicycles on epicycles, this Ptolemaic vision we hath wrought in sweat and silicon : ) ?

You do.

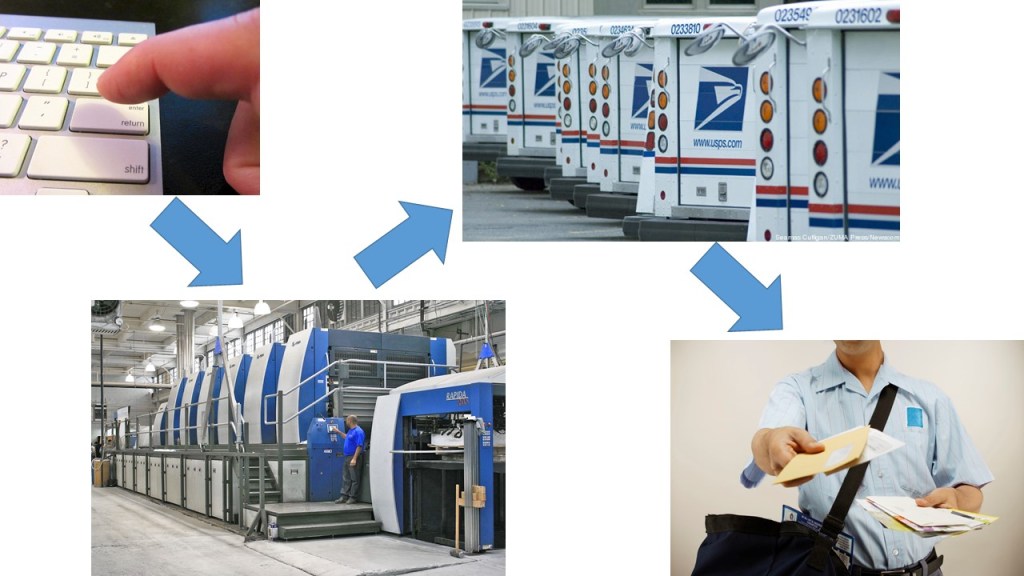

Software left to its own devices doesn’t do anything. It requires being set in motion, either directly, by a user taking a physical action through an interface that extends their will into and through the virtual world of software and back, eventually, to the meat world…

…or indirectly through a robot they have created which monitors some one or more signals, a clock, a barometer, a stock price, the water level in a reservoir, and, when the programmed conditions for action have been met, proxies their will to action.

These users are CONQUER’s ‘volitional entities’ – entities who have wills, who have goals, who can, on their own initiative, take action. They may be individuals or groups – Fowler’s ‘party’.

Distributed systems are, at the most fundamental level, information tools we build to help these volitional entities interact to achieve their goals.

‘Volitional entity’? Am I talking about agents? Yes, and no : ). If you are not familiar with the wave of agent technology that bubbled up after the rise of object-orientation in the 90’s, agent-based programming initially approached distributed solutions as a set of discrete agents – goal-directed components that act on behalf of another – tied together by messages. It evolved toward the use of autonomous or ‘active’ agents, agents that are able to respond not just reactively to explicit messages, but proactively to conditions in their environment. Like their simpler cousins cellular automata, active agents can collectively create complex behaviors from relatively simple rules. If we throw some machine leaerning, some AI, into the mix, we can build active agents that can do complex reasoning and adapt to changes in their environment to reach their goals.

The use of agent technology has followed a familiar pattern (and one I may be following here – we’ll see): a powerful conceptualization crystallizes, a kind of hypothesis, that looks to be a powerful model for designing software. We – the industry we – try to apply it in a top-down way, based on the conceptual design. We run into practical problems adopting it in a large-scale top-down fashion. Instead, the ideas fertilize the environment, and start to be incorporated bottoms-up, until we get to a point where they are widely implemented. The obstacles to the top-down approach – usually performance and scalability issues – become surmountable. At that point there is a renaissance of the ideas, a new look at their top-down architecture.

This pattern has happened with AI – twice. It happened with Complex Event Processing (pls see my post on that renaissance). This is happening with agents. We started with the hype of the 1987 Knowledge Navigator video from Apple. But multi-agent architecture failed to emerge as the dominant idiom during the 90s, despite strong foundational work. But look around now – agents are under every software rock you lift. Google News creating a customized news feed for you? Agent. Online job search bot that emails you new postings? Agent. We are at the cusp of a renaissance around agent architectures.

If we look at how agents are standardly categorized, there is a spectrum from simple stupid robots at one end to the intelligent agents of AI and on to humans at the other end. See Franklin & Graessers 1996 “Is it an Agent, or Just a Program?: A Taxonomy for Autonomous Agents“, or Tony White’s of Carleton’s lesson on agents.

With the concept of a ‘volitional entity’ I am making a higher-level distinction. Distributed software doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It ties together entities, enabling them to act and communicate to achieve their individual goals and objectives. Those actions, that communication, happen in frameworks of agreements among those entities, agreements of convention and covenant, agreements of practice and law, that govern their interactions, that create the guardrails within which they interact. Volitional entities are those entities who are able to enter into and abide by those agreements.

But the key thing is, volitional entities can always choose to do otherwise. The entities are morally, and usually legally, responsible for their actions or lack of actions.

It is those entities, those volitional entities, that must be our starting point in software design. The rest of the taxonomy of software agents, autonomous and otherwise? Minions of volitional entities who can grant the software agents authority to act on their behalf, but cannot defer the responsibility for those actions.

If you build and deploy SkyNet, or Colossus (the Forbin Project), and it ‘become conscious’ and launches the nukes, the post-apocalyptic war crimes tribunal will be coming for you.

Stay tuned.