This is the second in a series of posts (first, next, previous) in which I am exploring five key technology themes which will shape our work in the coming decade:

- The Emergence of the Individual Narrative;

- The Increasing Perfection of Information;

- The Primacy of Decision Contexts;

- The Realization of Rapid Solution Development;

- The Right-Sizing of Information Tools.

In today’s post, we will dive into the first in detail: the emergence of the individual narrative.

The Emergence of the Individual Narrative

As we all know, the consumer is quickly coming to the fore in the health industry. The pace is accelerating. We are all working to empower health consumers, to put them into the driver’s seat of their own care.

If we could wave a magic wand and know everything we wanted to know about a consumer to help this empowerment, what would it look like?

The so-called ‘social determinants of health’ are but a subset of the scope of knowledge: we would want to know not just their age and gender, their morbidities, their temperature and blood pressure, but also their moment to moment location, what they see and hear and smell and taste, who they meet, who they talk to, what music they listen to, what they read, what movies they like, when they fall in love, if they are in pain, what they text, what websites they see, their heart’s desire, how much money they make…

In other words, we would want a finely detailed, up-to-the-moment story of their entire life as told by an omniscient narrator (I hear it voiced by Morgan Freeman).

The narrative would capture and describe all of the changes to their inner states, such as emotions, beliefs, and friendships, and outer states, such as location, height, hair color, and marital status, over time.

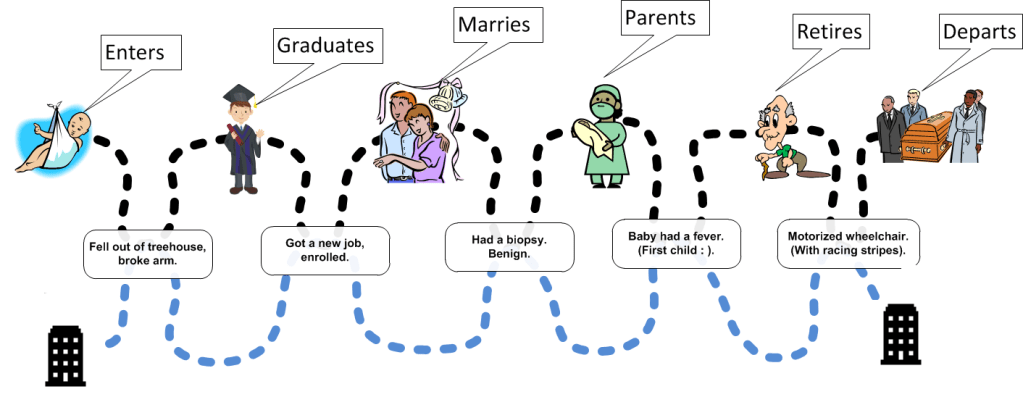

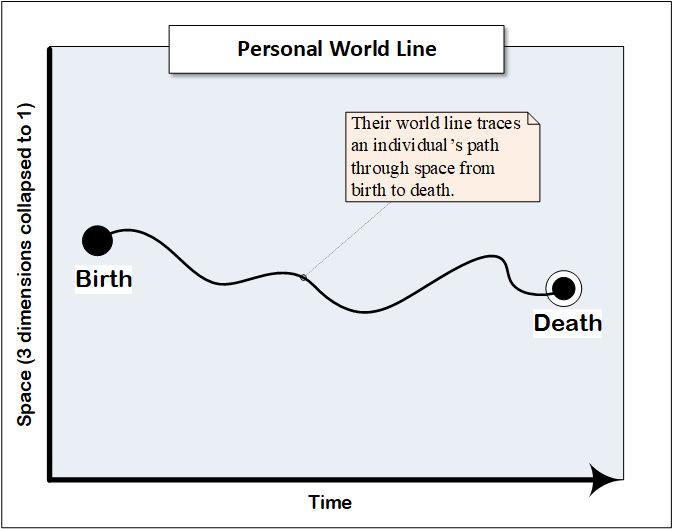

We could visualize their narrative using something called a ‘world line’.

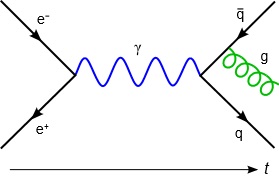

The concept of a world line comes to us from particle physics. It represents the passage of a particle through four-dimensional space-time and the events which influence its path. One early depiction is the ‘Feynman diagram’, invented by the famous bongo-playing physicist circa 1948. This one shows the collision of an electron and a positron, resulting in a photon (by tradition depicted as a lower case gamma ‘ɣ’) which emits a quark-antiquark pair, then spins off a gluon from the antiquark.

In his broadly syndicated comic ‘The Family Circus’ Bill Keane frequently illustrated young Billy’s adventures with the now famous dashed (world) line.

Inspired by Keane this is my illustration showing a cartoon version of a person’s world line in their potential lifetime of interactions with a healthcare business.

Consumer-Oriented Technology Trends

There are a number of discrete technology trends that are quickly converging toward the common consumer narrative-centric future: data matching, data provenance management, consumer 360 views, longitudinal health records, and customer journey mapping. A little analysis will reveal them to be the trunk, tusk, ear and tail of the consumer narrative elephant.

Data Matching

In the past couple of decades, master data management systems have been deployed at every significant enterprise. They exist to address critical data consistency issues.

With the advent of networking and the distribution and duplication of data to meet local performance needs, we created problems of data consistency across the enterprise. With the advent of interoperability, we are faced with problems of data consistency across organizations.

Data matching, the beating heart of ‘master data management’, is intended to fix that, to bring more consistency to data.

It does this by identifying ‘master’ data – the ‘nouns’ of a business, such as consumers, products, and providers – and matching the master data to link together data about the same entities.

Many systems go on the create so-called ‘best versions of the truth’, or ‘golden records’, by synthesizing the most accurate data about the entity from across the matched records.

The final necessary step on that evolutionary path is to share the truth – to synchronize the data with the systems from which it is sourced so they all match. Without that step, which many organizations fail to accomplish, the data is arguably more inconsistent, not less – there is one more data source that doesn’t match anything else exactly.

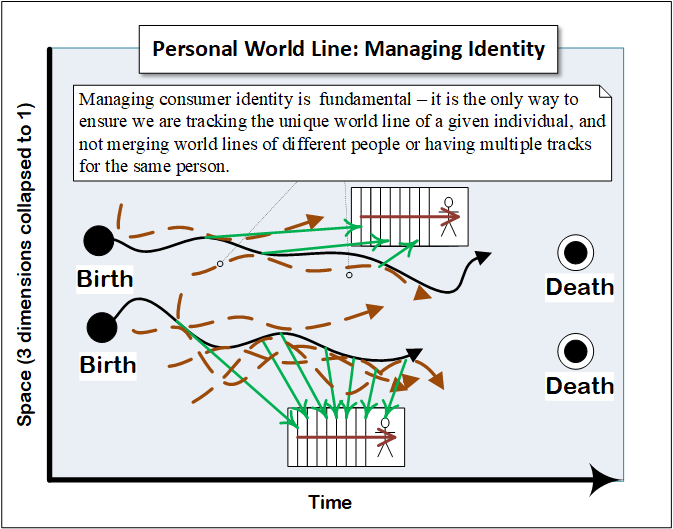

But now, with the rise of consumerism, we want to identify the same consumer across many systems. Consumer mastering per se is not a traditional master data management approach. Companies usually master customers from different customer databases, or products from different product databases. Most organizations don’t have multiple ‘consumer’ systems to master.

So what we are all doing is to take personal identifying information from many operational systems and purchased datasets – claims systems, care management systems, EHR systems, customer service systems, web and mobile apps, marketing data from Experian or Acxiom or Equifax or some other vendor – and create personal identity masters, consumer masters.

Based on industry presentations I saw and conversations I had at Informatica World, a leading master data management conference, a few years ago, many companies are well down this path.

The most recent approach to person matching is even more cognizant of the narrative nature of consumer data. Called ‘referential matching’, it uses not only current but historical demographics to increase the chances of matching records from two varied sources.

Awareness of the challenges with identity matching is not just rising across our industry, it is bubbling at the top of the pot. Individual identity is a key challenge in the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s draft Ten Year Interoperability Roadmap. The draft Senate HELP Committee bill on Health IT improvement commissioned a GAO study on improving patient matching. Identity issues in interoperability scenarios have been addressed in dozens of conferences. There are dedicated ‘identity summits’. Even the long-dormant National Unique Individual Health ID is getting some traction. There was an influential think piece by Barry Runyon at Gartner[1] a few years ago. Last year the House passed a rider on an appropriations bill which overturned the ban on spending on a national health ID that has been in place since the Clinton years. But it didn’t make it out of the Senate. The need for a universal patient identifier (the ‘universal’ part from the America is the World coalition) was actively discussed at the ONC national meeting recently in D.C.

(As I argue here, I believe we need a national health credential not an ID.)

But a consumer master, even based on referential matching, is only part way down the path to constructing the narrative we need. What is missing is the ability to sequence a comprehensive narrative across all of our consumer data. To get there, we need to add Time to the equation.

Consumer Data Provenance

Capturing and using Time in data is historically problematic.

Since the dawn of time (for software think the 1960’s) business software applications have been dominated by transactions. People in healthcare were patients, and members, and only useful – from a software perspective – in terms of being able to bill them for our time, determine their eligibility, apply their benefits and get everybody paid. As long as we had their current information to support operations we were good to go. (The same reasons the first generation of healthcare interoperability was transaction-centric.)

Timestamps of when things actually happened were not – and still are not – captured comprehensively. Instead the time the transaction is processed is captured, which is not the same thing.

For example, claims were not – and still are not – processed in the order that the care being billed was performed, which is the consumer’s perspective. They are processed in the order the claims are received, which the payer’s perspective.

This gap in capturing time first really came to light in IT when we started building data warehouses and data marts in the 90’s to support reporting and analytics. The most frequent way of structuring data in such a system is called a ‘star’ schema. A central hub of facts is surrounded by spokes, ‘dimensions’ of associated data that are used to slice and dice the facts.

One of those dimensions is always Time. It is obviously fundamental to any kind of historical reporting or predictive analytics. A lot of data warehouse work over the years has gone into fixing up a time dimension where it was originally missing or inconsistent in the operational databases from which we took the data.

We should have learned this hard lesson by now, and put Time into the very fabric of our databases. Unfortunately we still do this inconsistently. We do have some systems which are time-variant, meaning under the hood we track the history of all updates made to them. But that temporal aspect is not exposed in the views of that data to which current users are constrained.

But even with its time-variant design, the timestamping does not reflect when the events themselves occurred, such as a change of address, but when the update to the database happened – which is not at all the same thing.

To capture an accurate human narrative we must have the time of the actual events that influence their path.

In order to consistently capture the time when an event itself happens, we need a new approach called provenance management.

Without it we can’t have complete confidence in the consumer narrative we are capturing. In particular it is absolutely critical to the synthesis of best version of the truth consumer identity records in our master data management processes. Let’s look at an example to make this clear.

A person is observed, let’s call her Jill, and the value of some attribute of hers at that point in time is noted, say her hair color. It is only current as of the time of the observation. It is only as trustworthy as the observer. Was it more a strawberry blond, or Titian red? An orange red, or edging over toward auburn?

Now imagine that observer writes the color down, and passes the observation to another, who reads it, writes it down on their own paper, and passes it to another. And so on. Like in the parlor game ‘telephone’.

Now imagine three such observers, each seeing Jill at a different time – perhaps before and after her last appointment at the beauty parlor, which she entered as a brunette but emerged as the aforementioned redhead.

Now imagine you are the Hair Color master scribe. You are given three slips of paper from the end of three different Hair Color reporting ‘telephone’ paths, which originated with three different observers of Jill. You match them all together as being about Jill.

What hair color do you write down for Jill?

The practice of answering that, of choosing which particular value from a set of matched records we keep as the ‘truth’, is called ‘survivorship’ in Master Data Management.

Obviously, from our example, answering that correctly is a function of understanding the provenance of the observations. From whom, when, where, and how did they come?

The default rule for survivorship in MDM is ‘most recent’ wins. Which makes sense – all else being equal we want the most current values. But as we have seen from our example, the time that is important is not the time the observations are handed to the Hair Color master, it is the time the observer saw Jill.

And the trustworthiness of the observer matters. Did they have on their glasses? Are they colorblind? The accuracy with which the observation is written down is also important. Each time the observation has to be read, communicated, and written down again there is an opportunity for error – as anyone who has played ‘telephone’ knows. So even if an observer is more trusted, the overall ‘chain’ of transmission may be less trusted – one bad link can change the message.

Provenance management means tracking when a consumer state change actually occurred with as much accuracy as we can muster, and tracking the care that is taken to ensure that the state change, timestamp, and bona fides of the observer are all conveyed accurately and completely to us. This is akin to the ‘chain of custody’ for evidence idea we are all familiar with from police procedurals.

In the ‘Jill’ story above we were focused on survivorship – choosing which attributes to include in the golden record once we have matched records. But provenance is critical to the matching process as well. (There is an extended discussion of provenance in my knowledge strategy post here.)

The initial phase for any business or organization in granting a consumer entitlements – the permission and ability to do things with the business such as place orders – is to create a digital identity record and associate it with that individual in the world. Then credentials are associated with that identity record, and entitlements in turn are linked to those credentials.

The initial act of associating the identity record with the individual is called ‘data proofing’. Data proofing is the single-trust-domain (such as membership at a payer) version of identity mastering. It is where Identity, Credential and Access Management and Identity Mastering intersect.

The quality of data proofing varies widely. It ranges from none – where a simple email-based login grants you access to a website’s functionality – to rigorous, where an in-person interview is required and a background check of presented identity documents is performed, such as with passports.

The federal government has created a standard (NIST 800-63) for describing the quality of proofing. It has three levels of ‘identity assurance’, IAL1, IAL2 and IAL3, from weakest to strongest.

So as part of data provenance, when the data is identity related data, we need to understand the quality with which it was proofed.

We need all of the sources of data about a consumer to participate in an overall provenance scheme.

So ultimately what is needed to solve this are national – or at least industry – standards around data provenance.

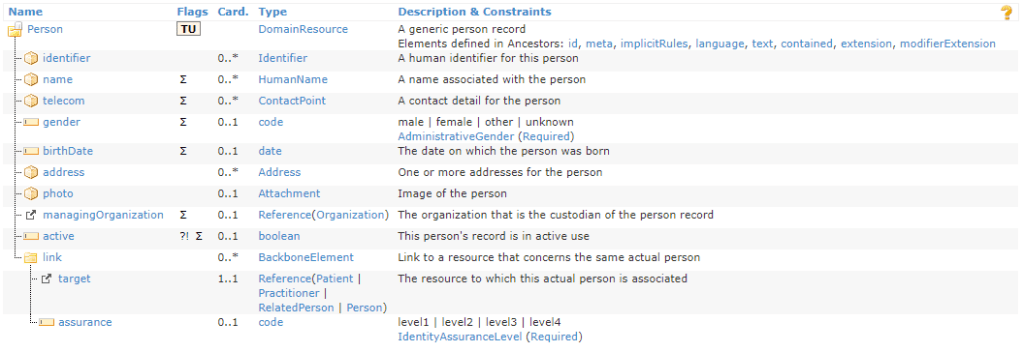

In that direction, the FHIR (the HL7 standards organizations new integration standard) person record includes a slot for the identity assurance level with which the person record is associated with another identity record (the four levels reflects the previous generation NIST standard).

Longitudinal Health Records

The ‘longitudinal’ in ‘logitudinal health record’ is just a data-science-y way of saying ‘chronological’. It is the real or virtual aggregation of the available health records – clinical, transactional, financial – on a common temporal axis. Why haven’t we had them for years? Because, as I pointed out above, we have not created time-variant databases, and have not linked together disparate operational records on common temporal axes. We started doing it in data warehouses in the 90’s, but those were mostly used for aggregate reporting. A temporal, longitudinal view is a different use case.

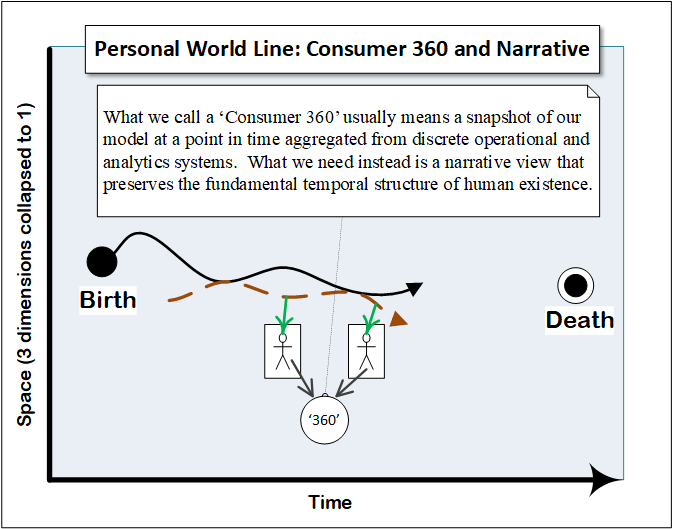

Consumer 360

Consumer 360 views, at least in their current most common conceptualization, are a stop-gap measure, a Band-Aid on the way to a true consumer-narrative focus. They provide a comprehensive read-only overview of all of the data we have about a consumer at a snapshot in time in a particular business domain. To the extent we may be able to usefully present some of that information in a narrative form – i.e. a timeline of claims history – it will make it easier to determine the narrative context.

But as we have seen, enabling seamless and transparent consumer experiences will require workflow integration around a comprehensive narrative, not just a read only view.

So Consumer 360’s will be vital, but will be transitional. They will morph into a comprehensive narrative view of the consumer’s world line from which we will be able to grab a state snapshot and type-of-data subset at any point in time.

Customer Journey Marketing

The most sophisticated and vigorous move toward realizing the new consumer narrative focus comes from Marketing – the Customer Journey Map.

Customer journeys are anchored in the way a customer thinks about their experience with a brand, not the other way around. Customer journeys capture each moment that matters, each event, each defining experience for a customer across for entire customer life-cycle, and customer journeys also define how a brand communicates with their customers at each of these moments that matter, across all touch points and all marketing channels.

Customer journey mapping puts all customer events ‘that matter’ and our communications with them in a narrative context. Salesforce MarketingCloud’s Journey Builder application is the most mature realization I have seen so far of this move toward the narrative focus.

The missing link journey mapping fills in is our need to understand and manage the consumer’s inner states – happiness, joy, frustration, embarrassment – in their engagement with us, not just their outer states.

Our orientation with consumers needs to be around their goals and objectives, and how we help them achieve them based on where they are now.

Consumer-Facing Applications Must Become Consumer-Centric

Consumer-facing applications need to become consumer-centric. And yes, it feels as silly to have to write that as it did for you to read it. But the sad truth is that today most consumer-facing applications and their underlying data are still transaction-centric, not consumer-centric. Partly that is baggage from the original ‘documents on desktop’ metaphor that still dominates graphical user interfaces.

We are backing our way into this consumer-centricity, fixing up the consumer interaction environment with additional information from across the enterprise via the ‘Consumer 360’ view.

Our systems themselves must inevitably become consumer-narrative based.

First, because the consumer narrative form is the appropriate common language for coordinating consumer-related workflows across the enterprise.

Most enterprises struggle to realize a single, common workflow system. Many of our third-party tools have workflow capabilities built into them. We need to take the approach of federating that workflow, gluing together the different workflow systems. And no matter what consumer-facing department or function is being integrated, the consumer and where the function fits into their narrative is fundamental.

The second reason for the transition to consumer-narrative based applications is in how much better that approach will be at supporting core service functions.

Customer service is largely about problem-solving. Customers have goals they are frustrated from achieving. Customer service identifies the obstacles and figures out how to work through or around them.

But from the consumer perspective, related things happen in sequence. And understanding why things have happened is always critically dependent on that sequence – sequence is at the heart of causation and explanation.

When we are problem solving with a consumer we always have to create a descriptive narrative. But right now most of our customer-facing reps have to infer that narrative from an array of static data and transaction references. That is unwieldy, and will necessarily change.

Putting our Consumer Together

Capturing an increasingly detailed consumer narrative is emerging as the fundamental new enterprise data focus of the next decade. Developing the capability to use it to understand consumers and predict their behavior is emerging as the analytics focus. Using the narrative to provide context for our interactions is emerging as the operational focus.

World Line Redux

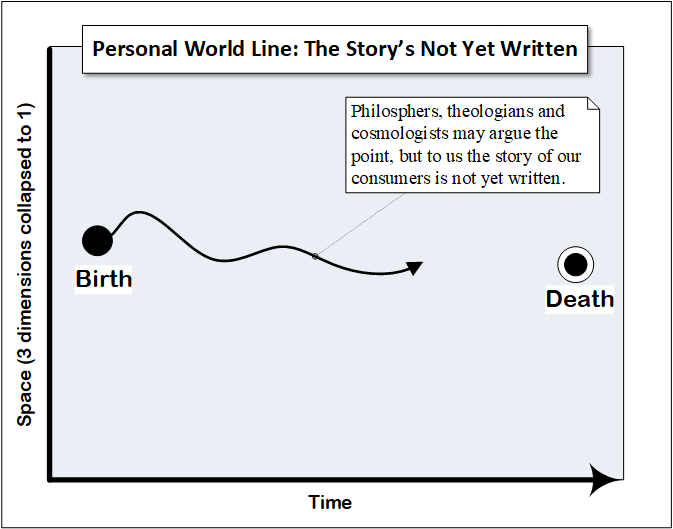

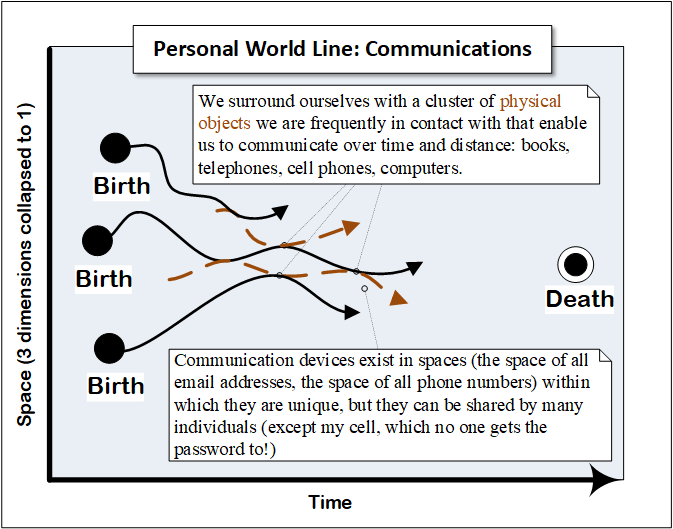

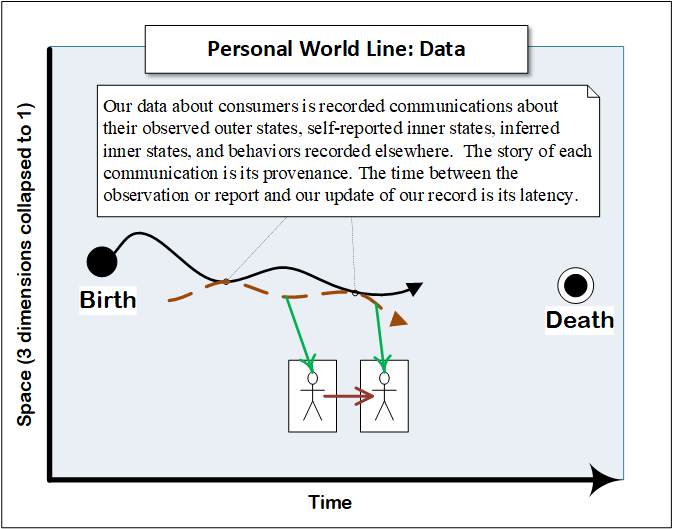

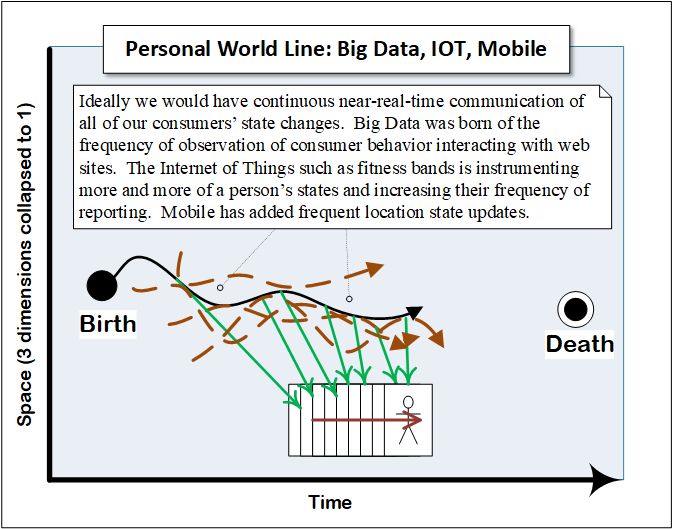

I introduced this section with the image of a consumer’s world line, the underlying form that describes their journey from birth to death. The following series of diagrams is intended to show how the various consumer-related elements I’ve discussed may be understood in relation to that world line.

Driving from Events

So what form does our consumer narrative take? What is it made up of?

The characters are Our Hero, the protagonist, the identity of the consumer, what Daniel C. Dennett would call the ‘center of narrative gravity[2]’, and those persons and organizations with whom they interact – including us.

The setting is the world, both physical and virtual, with which Our Hero interacts and through which they move.

The plot consists of events[3]. An event is a notable state change in an entity.

An event consists of the following elements:

- Pre-State – the state the entity was in before the event,

- Post-State – the state the entity was in before the event.

- Agonist or Agent – the outside cause of the event. Not all events have agonists unless one includes such constructs as ‘Father Time’ : )

- Time – the point in time or time span during which the event occurred.

The collected history of events is the plot until now. To that we add the likelihood of future events based on our predictive analytics.

The narrative is completed by our complementary analysis of the Hero’s motivations, our evolving inference of their inner states of which we have no direct knowledge, including their goals.

Our narrative lags behind their actual world line based on the latency with which we gather observations. Its accuracy is a function of the provenance of those observations. Its detail is a function of how finely instrumented their existence is. Its analysis is a function of our perspicacity.

Enter IOT and Big Data

The more types of events we record for a consumer, and the more of each type we are able to capture, the better our data and the more accurate our segmentation and predictive analytics.

To get more detail, to flesh out a person’s narrative, we will increasingly instrument their existence, capturing more of their state changes. That is at the heart of the impact of the Internet of Things with respect to health care. We will capture their temperature, their respiration rate, their galvanic skin response.

We will start to leverage the great body of ‘unstructured’ data. We will infer their mood from their purchasing choices, from their social media postings. And so on.

All of that fine-grained moment to moment data will add up to a huge volume of new data for us. A lot of the impact of big data for health care is going to be about building systems that can hold all of that fine-grained moment to moment narrative data and make it usable for analytics at both an aggregate and individual level.

The narrative structure will provide the data backbone of our future consumer systems.

Next up, we will dive into the next of our five themes: the increasing perfection of information.

Stay tuned.

[1] ‘Prepare for the National Patient Identifier Debate’, Barry Runyon, Gartner, 2/24/2016

[2] ‘The Self as a Center of Narrative Gravity”, Daniel C. Dennett in in F. Kessel, P. Cole and D. Johnson, eds, Self and Consciousness: Multiple Perspectives, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1992. Danish translation, “Selvet som fortællingens tyngdepunkt,” Philosophia, 15, 275-88, 1986. Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic565657.files/9/Dennett%20self%20as%20center%20of%20gravity.pdf

[3] Please see my series on events for more info.