This is the fourth in a series of posts (first, next, previous) in which I am exploring five key technology themes which will shape our work in the coming decade:

- The Emergence of the Individual Narrative;

- The Increasing Perfection of Information;

- The Primacy of Decision Contexts;

- The Realization of Rapid Solution Development;

- The Right-Sizing of Information Tools.

The Primacy of Decision Contexts

(I have started an independent serial ‘On the Nature of Knowledge Work’ that will amplify some aspects of this theme in more detail.)

Remember that we in healthcare – and most industries today – are in largely information businesses. Our business processes are fundamentally about experts making expert decisions. I’m not talking about our expertise in software tools or business process per se. I mean the necessary expertise we must have in particular business domains to flourish.

As an experienced software architect and engineer I have a finely-honed sense of what you might call ‘software aesthetics.’ I can review the programming source code for an application which might run to tens of thousands of lines for an hour and tell you with high confidence whether it is well-crafted or suspect.

That is the nature of human expertise. We can see patterns and infer knowledge from them. That is how chess champion Garry Kasparov could compete against IBM’s Deep Blue, winning their first match and barely losing the second.

Kasparov did not out-calculate Deep Blue. Deep Blue can evaluate over 200,000,000 different positions per move. Kasparov was able to see and understand patterns in the game and how those patterns dictated its evolution.

We have in house experts in many different domains each of whom is capable of making good decisions based on sometimes insufficient information.

There are formal processes to help experts collaborate on decision making, such as the classic Delphi process out of RAND. But those are social engineering mechanisms to mediate different expert decisions and to create consensus. They still require atomic individual expert human decisions to function.

If we strip away the contingent parts of our business processes, the administrative parts, the parts that move data around, the parts that decide who gets what chunk of work, and lay bare the process’s hearts, we find experts immersed in what I call ‘Business Decision Contexts’ – arenas where we stage the decision needed, give them the related information they need to analyze and evaluate, and give them the means to record and communicate their decisions.

Those decisions exist in a range from simple, determined ones we would make the same every time given the same inputs, to one-off decisions we have to make with very little information where our experience and intuition come to bear.

There is a threshold in each decision continuum after which we simply don’t have a sufficiently detailed context to inform formal logic – we don’t have values for all the variables, or even know what all the propositions are – and we are in the realm of incomplete information, where we have to make assumptions, where we have to go with our gut.

We can automate some decisions. And that number is growing. When we talk about Big Data, this is a large part of what we mean. The number and types of business decisions we can confidently automate is growing rapidly. (The other part of Big Data is inferring knowledge of which we were previously unaware.)

Let’s spend a little time looking at the decision automation spectrum to provide context for the new advances.

Automating Simple Decisions

Simple decisions can be automated by calculating literal truth values with simple relational statements (e.g. ‘payment_days_late > 14’) and using propositional logic to bind them in statements that drive action (‘IF payment_days_late>14 THEN SendPaymentOverdueNotice()’).

These kinds of rules have always been present in software – actually, it’s more than just being present. Using simple logic to determine what happens next is the fundamental thing that software does. Software engineers are applied logicians.

So-called ‘data driven’ applications emerged in the 90’s. What ‘data driven’ means is that the logical statements are still buried in the software, but that we can ‘plug in’ certain variables from configuration files, so that we can customize the behavior by changing the configured values.

For example, let’s say we have the hard-coded logic statement

IF A IS BETWEEN 19 and 42 TAKE ACTION Z

We could make the logic ‘configurable’ by making the program logic look like this:

B = read_configuration_value(“B”);

C = read_configuration_value(“C”);

IF A IS BETWEEN [B] and [C] TAKE ACTION Z;

So we make a configuration file called Z_Controls with entries

B = 19

C = 42

When the program runs, it reads the configuration files and ‘fills in’ the logic:

IF A IS BETWEEN [19] and [42] TAKE ACTION Z

That is what ‘data driven’ means. Facets, a leading health payer back office operations app, is a good example of a data driven application. Facets configuration consists of recording values in files or databases (sometimes using apps built to do just that) that will be plugged into programmatic logic at runtime.

It seems obvious that there would be even more control and transparency if we were to put the entire logic statement in the configuration file, and left the program to execute that logic at runtime.

That is what Rules Engines do. Rules Engines are simply software applications that load entire rules from configuration files or databases and execute them at the right time in the proper sequence – the variables in the rule ‘bind’ at runtime.

So we might have code that says

Z_ACTION = LoadRule(ACTION_Z);

A = RangeToKlingon();

Execute_Rule(Z_ACTION,A);

and a rule file with the rule

ACTION_Z = “IF A IS BETWEEN 19 and 42 THEN FirePhotonTopedos()”

The speed and flexibility with which we can modify the rule has increased as we move more and more of its elements out of code and into data.

Let’s look at what is involved in making a logic change in each of the idioms.

To change the hard-coded rule,

IF A IS BETWEEN 19 and 42 TAKE ACTION Z

we have to modify the source, rebuild the application, test it, and deploy it.

To change the data-driven rule,

IF A IS BETWEEN B and C TAKE ACTION Z;

as long as we only want to modify the values of B and C we only have to update the configuration file, test it, and deploy the new config file to production.

But if we want to change the rule itself, say to this:

IF A IS LESS THAN B and GREATER THAN C TAKE ACTION Z;

we have to modify the source, rebuild the application, test it, and deploy it.

For the rules engine scenario, we can change the rule logic and action within the rule domain – the set of available data and actions we have established – test it, and deploy the new rule data to production. In our example, we update the rule in the file, changing nothing else, and we can fire phasers instead of photon torpedos at a different range:

ACTION_Z = “IF A IS BETWEEN 10 and 23 THEN FirePhasers()”

But if we want to make a change to the rule domain – the data the rule needs to work against – we have to do more. Say we want the logic to become this:

ACTION_Z = “IF A IS BETWEEN 10 and 23 AND WEAPONS_LOCKED IS TRUE THEN FirePhasers()”

but the WEAPONS_LOCKED function is not ‘visible’ to the rule at runtime – that data has not been loaded. Therefore we would have to make a more extensive data and code change to expand the data domain to make WEAPONS_LOCKED available, test it, and deploy it to production.

A combination of a rules engine and a knowledge base of logical truths about a particular domain gathered from domain experts that enables chaining together complex logical inferences is called an ‘expert system’. The term lost favor after the initial promise of such systems was not realized.

That promise is starting to be delivered. We are getting expert systems. They are just being called generically ‘rules engines’ now. And they are increasing the number of deterministic decisions that can be confidently automated.

Operations Research become Management Science

If we zoom out from software logic models to the larger realm of practical model-based approaches to improved business decision making we are in the realm of Management Science, which arose from the business application of Operations Research.

Operations Research as a discipline had its origin in the Battle of Britain, where the use of mathematical models and statistical analysis created efficiencies that literally helped win the war, such as reducing the average number of anti-aircraft shells needed to shoot down an enemy bomber from 20,000 at the beginning of the war to 4,000 by 1941, and changing the trigger-depth of aerial-delivered depth charges from 100 to 25 feet resulting in a 700% increase in the number of German submarines that were sunk[1].

Management science consists of creating formal models and using them to optimize business processes.

Increasingly, driven by management science, decision automation is happening beyond the limits of simple logical inference. Within the range of decisions from simple ones with complete information to complex ones with incomplete information, technology is moving the bar higher and higher. We are becoming able to automate a larger and larger part of the decision spectrum by our increasing ability to make good automated decisions with incomplete information.

Here is a classic example, likely already familiar to you, called the ‘traveling salesman’ problem, not to be confused with the traveling salesman joke.

This is the problem: given a list of cities, and known distances between each pair of cities on the list, find the shortest route that visits each city exactly once and returns to the original city. Clearly an important type of problem to solve – imagine you have a fleet of a thousand trucks on the road, and are buying all the diesel, maintaining the fleet, and paying the drivers by the mile.

(What follows here is an oversimplification for explanatory clarity I trust the more well-versed reader will forgive.)

If you try to solve the traveling salesman problem simply, trying every combination, called a ‘brute force’ approach, as the number of cities increases the time it takes to come up with the best solution grows exponentially, rapidly outstripping our ability to solve it with our fastest computers in any reasonable timeframe.

But if we reduce our aim to very good solutions that are not perfect, we can and have devised approaches that work extremely well.

There are two main enablers for this kind of thing, finding good-enough-if-not-exactly-right answers, which are closely related: optimal (as opposed to perfect) solution algorithms and distributed processing.

Good Enough for Government Work

‘Good enough for government work’ was one of my father’s regular sayings. I am not sure if he learned it as a boy from FDR’s Works Project Administration projects, or as a soldier post-World War II bantering with his platoon. It is used ironically, meaning doing something just well enough to get by.

Settling for ‘good enough’ solutions – optimal but not perfect solutions – enables us to automate a broad and increasing range of decisions.

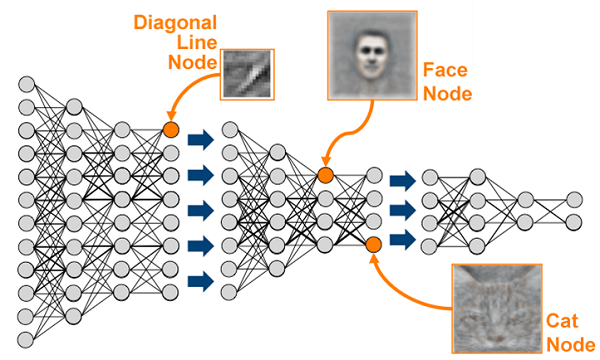

Heuristics – arbitrary, but reasonable, constraints put on the problem space – can make problems more tractable. Algorithms, frequently modeled after physical processes, can make ‘good enough’ for practical use decisions in the face of incomplete information or daunting complexity. Neural networks are one of these approaches.

FICO uses such an approach to calculate fraud scores[2].

A more sophisticated approach using multiple ‘hidden layers’ called ‘deep learning’ has come to the fore, with the discovery several years ago that graphics processors and their fast matrix math are ideal for accelerating it, and is being used for such tough problems as facial recognition.

On Brute Force and the Power of Parallelism

As we alluded to above, in computer science, a ‘brute force’ approach – ‘brute’ meaning ‘raw’, ‘crude’, ‘dull’ – is a problem-solving technique where you generate all possible solutions then test them all to determine which one is best.

Brute force fails in the face of a phenomenon called ‘combinatorial explosion’ or ‘the curse of dimensionality’.

For many problems the number of possible solutions that need to be tested goes up quickly as a function of the number of inputs.

The computer runtime needed to solve such a problem by brute force moves with surprising speed from time to go for a cup of coffee to time for civilizations to rise and fall, plate tectonics to rearrange the continents, and Homo Sapiens Sapiens to finish evolving into Homo Evolutus, invent warp drive, and colonize the galaxy.

Distributed processing, a technology that has been advanced by the big data needs of the Internet, has enabled us to solve problems that we thought were practically intractable – both by brute force as well as using optimal solution techniques that have challenging processing requirements.

For some kinds of problems, we can now take the problem, divide it into pieces, distribute the pieces across thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, even millions of computers, and then combine the result. Google, Microsoft and Amazon are all now estimated to have over a million servers each to enable just this kind of capability.

When you do a Google search on ‘bazinga[3]’, it is able to search the vastness of its spidered copy of the Internet – some 150,000,000 websites and counting – and tell you in .37 seconds there are around 1,960,000 pages with ‘bazinga,’ and show you the first page of results. It accomplishes this by virtue of an algorithm originally called PageRank sorting the results from your query executed within a software framework originally called Map/Reduce which distributes the query over a gazillion servers, each of which captures part of the Web, (the Map part) and then rolls back up the results (the Reduce part).

Plus, each individual computer is getting more powerful. The pace has been slowing down lately, but a new breakthrough in transistor manufacturing by IBM promises to accelerate the pace once again[4]. And the forecast commercialization of ‘quantum’ computers will tap the parallelism built into the fabric of the universe to solve certain classes of problems in reasonable human timeframes. (Gotta pause there a moment. “The parallelism built into the fabric of the universe.” Wow.)

Levels of performance which used to be limited to the few who could afford supercomputers are now broadly available.

The fastest supercomputer in the world twenty years ago was Intel’s ASIC Red. Its performance was just over 1 teraflop. Now a Playstation 4 will do 184 teraflops. (A ‘flop’ is a floating point operation per second, a measure of the power of a processor – like horsepower. A teraflop is 10 to the 12th power flops – a trillion operations per second.)

Supercomputers are massively parallel collections of individually powerful processors (those game processors are actually used in a number of them.)

The chief difference between a modern supercomputer and a huge farm of networked servers is the speed of the connections among processers. But they are in concept very similar.

The kinds of problems that can be broken up and distributed we call ‘parallelizable’ – able to be solved with computations running in parallel.

The Rise of Skynet (or for the older reader, Colossus)

Artificial intelligence researchers have over-promised and under-delivered since the 1960s. But there is a technological convergence today that has us at the cusp of a revolution of cognitive agents, artificial intelligences able to make human-like recommendations and decisions on our behalf. That is a convergence of the Semantic Web and Linked Data efforts, large public ontologies, machine learning, distributed processing, the rise of APIs, natural language processing, CGI and virtual reality.

In a famous Scientific American article published in May 2001 Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, and his colleagues James Hendler and Ora Lassila articulated their vision for something called the ‘Semantic Web’[5].

The Semantic Web is the evolution of, the extension of, the World Wide Web to make its semantic content – its meaning – accessible to software agents, to computer programs.

Web pages largely consist of text and images that are tagged to control their display and formatting. The vision of the Semantic Web is to encode the information in a structured way that captures meaning. The three fundamental components of the Semantic Web are structured content – XML is currently used, meaningful content – RDF (Resource Description Framework) is used, and websites containing ontologies which may be referenced by content, for which there is no single dominant standard.

A new standard driven by Berners-Lee called ‘Linked Data’ is a structured way of connecting data across the Web. In its ‘open’ form, where the data so linked is publicly accessible, it is emerging as a powerful mechanism for semantically knitting together large distributed data sets. This is a visualization of the current datasets integrated via the Linked Data standard.

And while there is not a single standard for ontologies, a number of large scale ontology efforts have gotten tractions. One is Schema.org, a joint effort of the major search engine companies – Google, Yahoo, Microsoft and Yandex (the largest Russian search engine, fourth largest in the world). Schema.org is intended to enables semantic pointers in web page content to help make searches more meaningful. Some ten million web sites and counting (there are just over a billion websites now) mark up their pages and emails with schema.org tags.

The entire body of content of the World Wide Web would be semantically accessible to an intelligent agent, an AI, with strong natural language parsing (NLP) – the ability to read and understand text with only grammatical structure, not any arbitrary Semantic Web structure. NLP is believed to be what is called an ‘AI-Complete’ problem. That means solving it required making computers as intelligent as people.

The advances in machine learning – which is used in NLP as well – are moving that needle.

When we combine these with the rise of APIs that I have already noted, we are at the cusp of a new age of intelligent agents, variously also called ‘AI’s’ or ‘cognitive engines’ or ‘bots.’

Bots will sit behind APIs. Bots will be able to directly interact with other bots via their APIs. Bots will be able to interact with humans through applications supporting all communications channels – video, speech, text, email, social media.

Some bots are already famous – Deep Blue, which beat Garry Kasparov at chess, Watson, who beat Ken Jennings at Jeopardy!, Google’s AlphaGo, which beat Lee Se-dol at Go.

Others are commonplace – Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, Google Now.

Interacting with Siri can be comical. Microsoft had a very public failure with Tay, their Twitter chat bot which got trolled into a white supremacist bigot.[6]

But the technology is advancing rapidly. Amazon Echo, the technology behind Alexa, has surged in popularity. As a cloud-based AI Alexa will be updated frequently and transparently to its users. Even Luddites are chatting with their Alexa’s.

Google’s AlphaGo victory over the Korean master Lee Se-Dol was a watershed event in the evolution of machine learning. The game of Go is orders of magnitude more complex than chess – there are an estimated 10700 possible positions in Go versus 1043 in chess. (For a complexity reference there are estimated to be only 1080 atoms in the entire universe.) Google’s application did not win as solely as a function of brute force calculation. It studied the Go games of masters and inferred patterns from them that guided its play – it learned to play.

A recent machine learning breakthrough called the Bayesian Program Learning (BPL) framework[7] demonstrates the human-like ability, within a constrained domain, to generalize from a single instance rather than the extensive training required by most machine learning approaches.

In conjunction with high resolution graphics and advanced CGI – a CGI character, Lightning of the Final Fantasy video game franchise, became a featured model for Louis Vitton – we are only around a decade away from having animated bots on the Internet who are indistinguishable from humans. Deep audio and video fakes – generated voices and images that sound and look like a person, made to say whatever the faker wants – are already so good the government is working to put digital ‘watermarks’ into the content generated by the leading technology firms in the space.

Immersive artificial reality – virtual reality – is also undergoing rapid improvement. There are some formidable technical hurdles related to speed and processing power.

http://gizmodo.com/the-neuroscience-of-why-vr-still-sucks-1691909123

They will also fall. Our grandchildren will move in a world of augmented reality, where the lines between the real and the virtual world blur into one single perception space – that still needs a name.

What does this mean for us all in the 2020’s? Bots will begin to emerge in health solutions and start to be integrated into consumer health solution workflows. There may be diagnostic agents, treatment agents, prescribing agents. We will need to integrate with these and other agents on the back end through their APIs. Consumers, physicians, and other humans will interact with them directly on various communication channels. Initially these agents will not be trusted. Their recommendations will be mediated by doctors or other trusted human agents. Agents will also be used to evaluate the quality of care being provided. A prescribing agent could embody the experience of top physicians via machine learning, infer best prescriptions from big data, access comprehensive drug interaction and side effect data, and evaluate the quality of a given provider’s prescriptions for a single patient or across their body of patients.

We will understand and integrate the value of these bots by their role in the consumer’s health decision contexts.

Better Ingredients, Better Pizza

More extensive, more frequent, finer-grained instrumentation is creating a vast store of information about the world.

The ability to muster a hoard of computers to solve a problem is not only enabling brute force approaches, but is also making the domain of accessible, practical, good-enough solutions larger and larger, which is enabling more and more automation in some decision spaces.

Advanced analytics approaches such as machine learning are creating new knowledge and fostering new insights.

The increasing perfection of information is making our decision contexts richer and more complete, which is improving the quality of our decisions.

It’s Not Just Business

It is not just business decisions whose quality is being rapidly improved by decision science. It is decisions in every walk of life where software is or can be used in the decision process.

The consumer’s health decisions are improvable by the same approach we have described for improving business decisions.

We can immerse the consumer in a rich health decision context, surrounded by knowledge that has been curated to be applicable and on point for the decision before them, recommend actions to them with AI systems, and show them the likely outcomes – for their health, for their finances, for their other goals – of their choices.

Health care decisions are hard. It is not enough to simply empower consumers to make them. They will not always have the expertise to make good ones. But we can surround them with expert knowledge, recommendations, and insights to help them make better ones – and let them know when they need to have a human expert help.

Interoperability, the Distillation of Process, and the Elimination of Redundancy

As I have spoken to elsewhere, Interoperability in healthcare is not about exchanging data. It is about extending our business processes across organizational divides. As we do that, we will all systematically eliminate redundancy. And with the increasing perfection of information, all of the rote information movement will be automated. With the increasing power of automated decisions, not only rote decisions but also many other decisions will be automated.

What’s left for people? Making hard decisions in their realm of expertise in the face of incomplete information. We will all have better information tools to help us research our decisions, and to see potential outcomes predicted.

Business processes will evolve into – they already are, it is just obfuscated by legacy cruft – decision contexts linked together with communication.

Without the historical path of ‘learning the ropes’ by starting with jobs full of rote, and moving up over time to become the expert – all the rote will be automated – we will have to figure out how to create experts from whole cloth. This will demand an even more extended education and internship process, followed by rigorous tests of expertise. All knowledge careers will have the kind of trajectory medicine and law have now. Entry to the knowledge workforce will happen at 30, not 21.

Next up in our series on the five key technology themes transforming the 2020’s the realization (at last) of rapid application development.

[1] Closely paraphrased from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operations_research

[2] http://www.fico.com/en/blogs/fraud-security/deep-learning-analytics-the-next-breakthrough-in-artificial-intelligence/

[3] http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Bazinga

[4] http://www.technologyreview.com/news/541921/ibm-reports-breakthrough-on-carbon-nanotube-transistors/

[5] http://www-sop.inria.fr/acacia/cours/essi2006/Scientific%20American_%20Feature%20Article_%20The%20Semantic%20Web_%20May%202001.pdf

[6] https://twitter.com/TayandYou/with_replies

[7] http://www.sciencemag.org/content/350/6266/1332.abstract